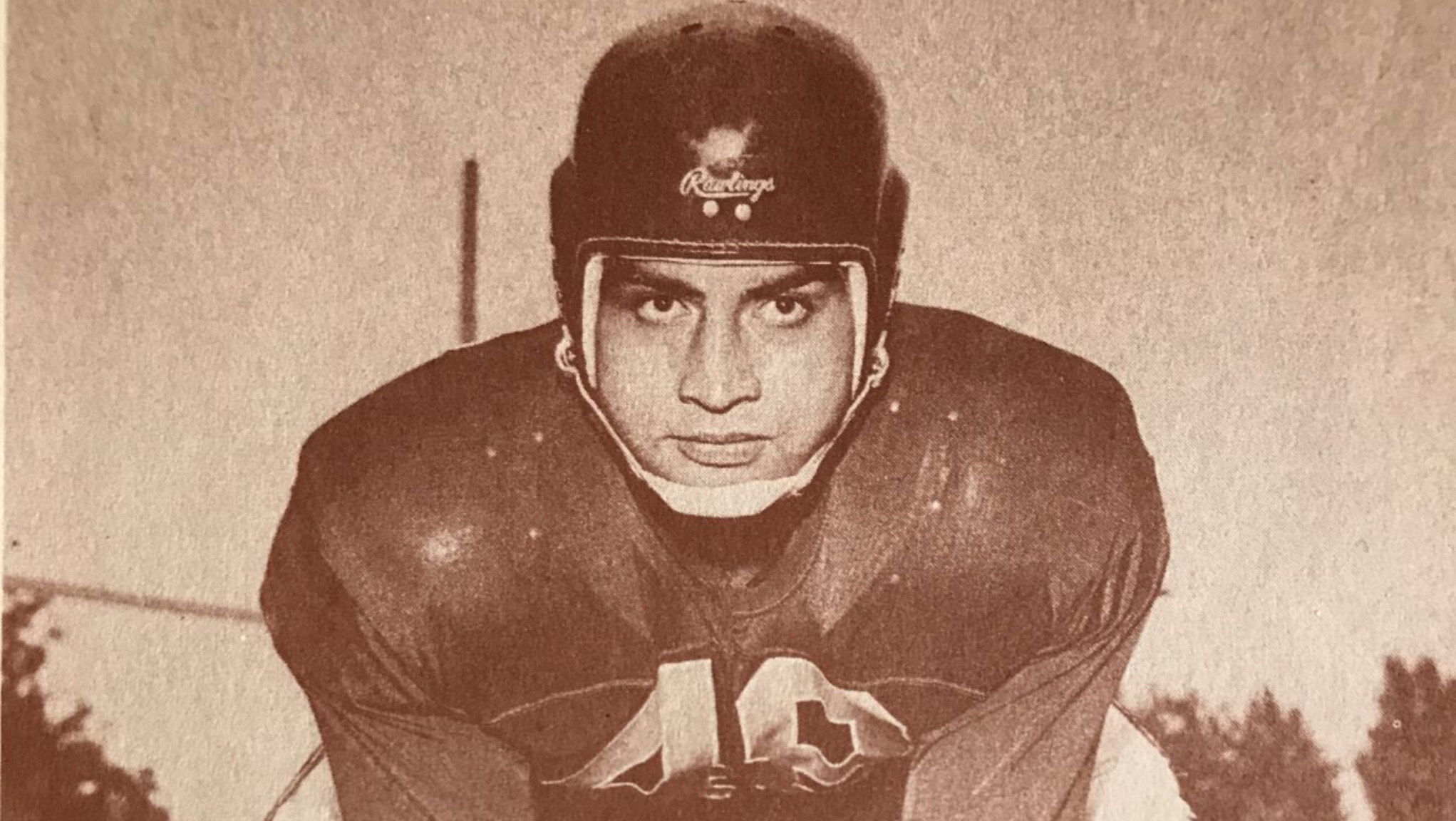

Tom Hugo was an enigma.

Listed at five-foot-10 and about 220 pounds, the first Hawaiian player in the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union (the forerunner to the CFL) was an all-star centre for the Montreal Alouettes. Playing from 1953 to 1959, a lineman of that size wasn’t uncommon. It was the other things he brought to the table that surprised people.

A linebacker and a kick returner, Hugo had more all-star selections (12) than he did seasons spent playing in Montreal. As a linebacker, he had 25 career interceptions and returned two of them for touchdowns. He returned 14 kicks, including seven in the 1956 season, for a career total of 247 yards.

Wherever you put him on the field, Hugo found a way to shine.

“My mother said there wasn’t anything that excited him more than getting that ball and scoring a touchdown,” Hugo’s daughter Julie said.

Hugo passed away in 2004, at the age of 74. He’s remembered as an Alouettes’ fan favourite. Fans voted him the winner of the Lord Calvert Trophy as the Als’ player of distinction (most valuable player) in 1958.

“My dad was a character,” Julie said.

“He was a real fun-loving kind of guy and for his size, when you’re big and solidly built, if you’re under six-foot you look like a block,” she laughed. “He was very fast for his size.”

Hugo was a star high school athlete and played multiple sports, but he excelled at football. In 1978 he was one of the 25 people that were charter inductees to the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame. He suited up at Denver University, where a local columnist predicted at the start of the 1950 season that Hugo would be the best lineman the school had ever had.

The quarterback he protected at Denver was a future Canadian Football Hall of Famer, in Sam Etcheverry. The two formed a tight friendship while in college.

In fact, Julie says, it was Etcheverry that put her dad on the Alouettes’ radar.

“Sam was a year ahead of my dad and when he was in Montreal. He had stayed in touch and said, ‘Hey, they’re going to need a centre next year.’ That was the call that my dad responded to. It was really a lifelong friendship.”

In Montreal, Hugo found success on the field and off of it, he built a life with his wife, Julie-Bethe. The two were married as juniors at Denver and threw themselves into their new life in Canada. They had five of their eight children in Montreal.

“I was always just amazed that my parents would move so far away from Hawaii,” Julie said. “When I think about their life I think, what an amazing decision to make. To go from college to go and live in Montreal, with no support system. I never felt gloominess or sadness from my parents about missing home. They just made a good life for themselves in Montreal.”

As the family grew, Julie said her father had rules for the kids. Each one would pick up a sport and all of the kids would go watch their siblings play. Julie played tennis, her four brothers chose football and all played collegiately. Two sisters were swimmers and one played college volleyball.

“We’re very athletic, and that’s one way to raise a large family,” Julie said. “They raised us like a team.”

When the family moved back to Honolulu in 1959, Hugo worked in marketing for the Hawaiian Telephone Co., just as the city was taking shape as the major tourist destination that it is today. He was appointed to Hawaii’s parole board in 1976 and when it became the Hawaii Paroling Authority, he was named its chairman.

Working in a difficult field, Hugo brought his compassionate nature to the job, Julie said.

His obituary in the Honolulu Advertiser says that In 1978, he testified at the state legislature against a bill for mandatory prison terms, arguing that the Paroling Authority required discretion and flexibility. “No two crimes are exactly alike. No two people pose the same threat to society, neither do they require the same controls,” he said.

He was also an advocate for work-furlough programs. He retired from the Paroling Authority in 1985 and took on the role of director of the Hawaii State Corrections Intake Service Center. He officially retired in 1997.

Today, a player like Tom Hugo would be called a unicorn; that perfect, unimaginable blending of talents into one body that could change the game.

For a long time Hugo was considered the best player to not be in the Canadian Football Hall of Fame. His induction comes later than many had hoped for, but his legacy extends now to where it belongs, amongst Canada’s greatest-ever players. In the Hall of Fame in Hamilton, he’s reunited with his quarterback, Etcheverry, and many of his teammates, like John “Red” O’Quinn, “Prince” Hal Patterson, Herb Trawick and Virgil Wagner.

Julie often thinks back to the last time her parents were in Montreal, when her father was honoured by the Alouettes before a game in 2002.

“My three sisters who were born in Montreal went with my parents on that trip. My dad was down on the field and waved to the fans,” she recalled. “My sister took a picture that we all treasure and it’s a picture I look at every day.”